On January 9, 2020, a paper entitled “Gaze Response to Others' Gaze Following in Children with and without Autism” was online published in Journal of Abnormal Psychology (top journal of clinical psychology sponsored by the American Psychological Association) by Dr. Li Yi’s group at the School of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences. This study explored time-course differences in the reciprocity of social gaze patterns in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and in typically developing (TD) children around 7 years old by using a computer-based gaze-contingent eye-tracking task.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by social impairments and repetitive behaviors. Considering the important role of attention to faces and eyes play in social communication, Yi’s group used to explore face processing in children with ASD, especially the mechanisms of diminished attention to eyes or eye avoidance in these children.

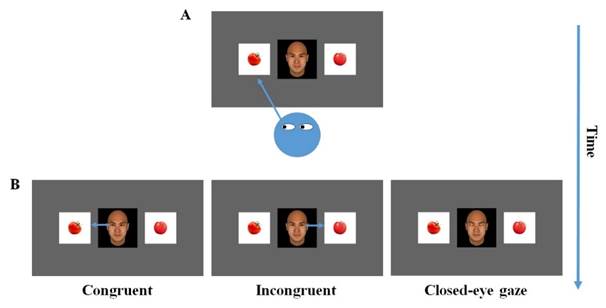

However, only studying eye avoidance is not enough, it is also important to know how ASD children gain social information from others’ eyes. One such information contained in the eyes is gaze direction, which can reveal people’s mental states. In order to study whether children with ASD could understand and follow others’ gaze in a reciprocal context, Yi’s group used the interactive eye-tracking paradigm based on the gaze-contingent approach. In a trial, children were instructed to look at one of the two objects they preferred (Fig. 1A). Then, the virtual face in the center of the screen began to shift its gaze to look at the object children looked at (First-looked at object, FLO) (congruent condition), to shift its gaze to look at another object (nonfirst-looked at object, NFLO) (incongruent condition), or to close its eyes (closed-eye gaze condition) (Fig. 1B). Yi’s group mainly tested three questions: (1) how children attended to the objects in response to others’ gaze following or failure to follow, (2) whether children with ASD displayed atypical attention to the partners’ eyes during joint attention, and (3) whether attention to eyes influenced subsequent attention to objects.

Fig. 1. Experiment design. Children (blue face) initiate a joint attention by looking at one of the two objects (A), then the virtual face shifts its gaze (1.2 seconds) to follow the children’s gaze in the congruent condition, to disregard the gaze and look at another object in the incongruent condition, or to close its eyes in the closed-eye gaze condition, followed by 3 seconds of the final gaze phase, during which the face gazing at the object continued as a still frame (B). Data from phase B were analyzed.

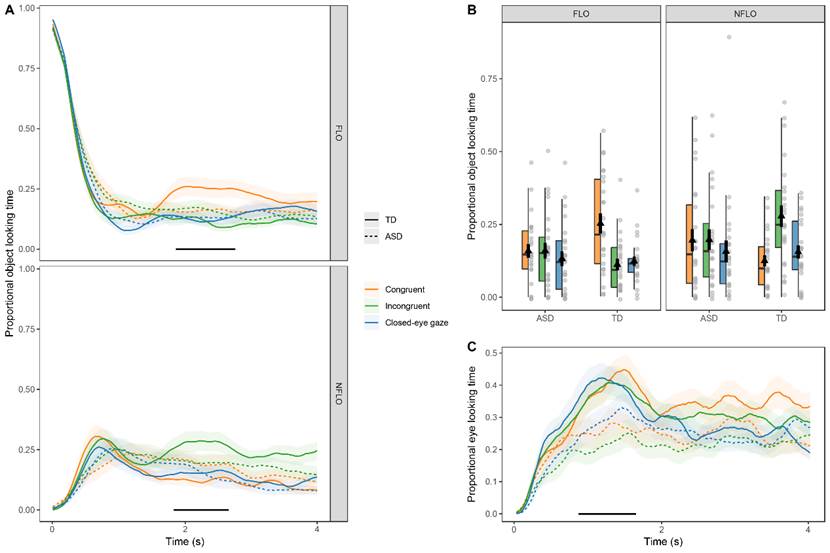

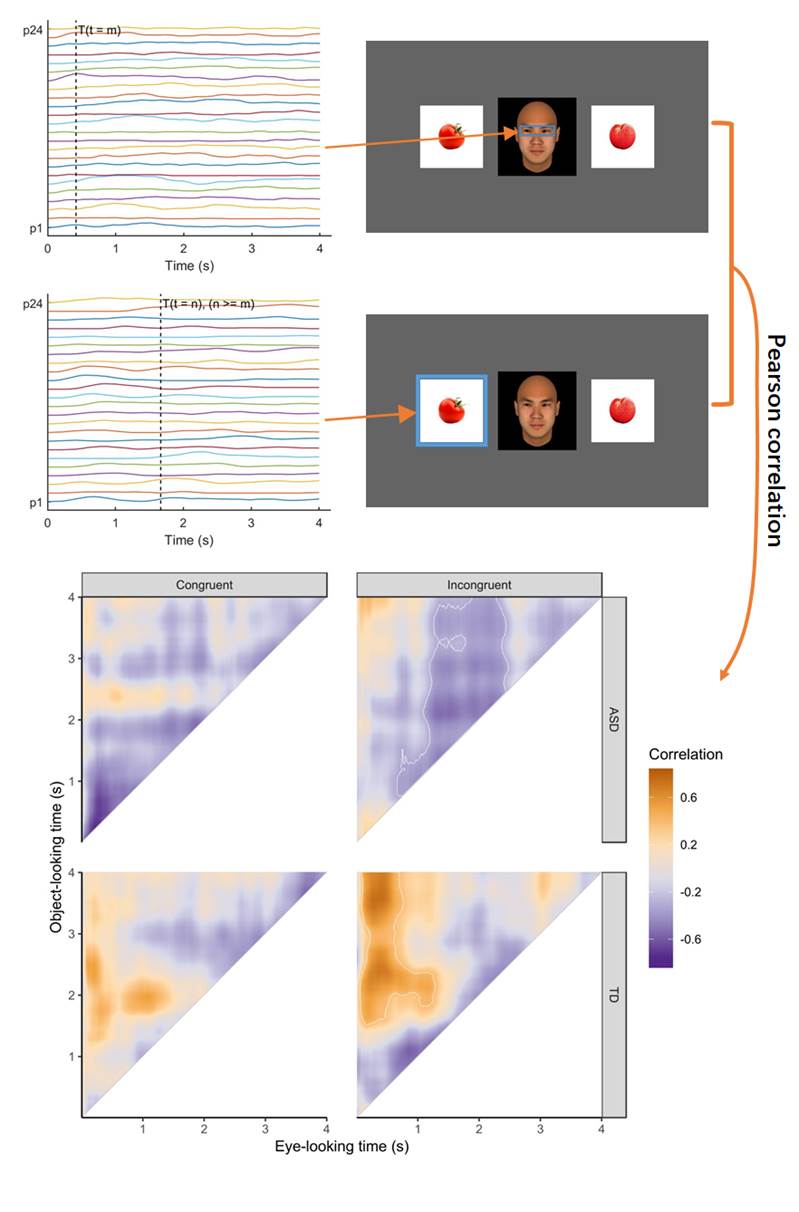

The results showed that (a) TD children, but not children with ASD, showed different object-looking times across conditions, suggesting TD children can follow others’ gaze and are sensitive to virtual faces’ following their gaze (Fig. 2A & 2B); (b) children with ASD looked at eyes less than TD children (Fig 2C); and (c) eye-looking time improved subsequent object-looking time in TD children, whereas it interfered with object-looking time in children with ASD (Fig 3). This result suggests that eye-viewing may be confusing or distracting for children with ASD, rather than being informative about the object for TD children. Our findings imply that interventions that address social impairments in children with ASD should target not only improving their eye contact but also promoting an understanding of the social meaning of eyes.

Fig. 2. Results of the eye- and object-looking time. Time-course of proportional object-looking time (A) and eye-looking time (C). Time series signals of proportional AOI-looking time were created by calculating the proportional trial towards a particular AOI relative to the total number of valid trials for each data point. Multiple comparisons were corrected by using a cluster-based permutation test. The black horizontal line illustrates the cluster of time when the Condition x Group interaction effect (A) or Group main effect (C) is significant. The shaded area indicates standard errors. Time zero is the start of the face’s gaze shifting. (B) Boxplot of object-looking time during significant time periods revealing interaction effect in Fig 2A, with each triangle representing mean value, each thick black vertical line representing error bar, and each point representing one child.

Fig. 3. Correlation results. For each data point of the time series signals, we correlated proportional eye-looking time across participants at time m with proportional looking time on the gazed-at object (FLO in the congruent condition or NFLO in the incongruent condition) at time n (0 ≤ m ≤ n ≤ 4 s) (top panel). This results in a 480 (data points) × 480 (data points) upper triangular matrix (bottom panel). Each value in the matrix represents a correlation coefficient between eye-looking time pattern at time m and looking time on gazed-at object at time n (0 ≤ m ≤ n ≤ 4 s). That is, correlations are between the proportion of time spent looking at eyes and proportion of time spent looking at objects at any given time point throughout the trial, with the restriction that eye-looking time happens before object-looking time. Areas showing significant correlations are delimited by white borders (multiple comparisons were controlled by using the cluster-based permutation test). Areas of interest (AOIs) for the object and eyes (within the blue rectangles) are also illustrated in this figure.

Qiandong Wang, a fifth-year doctoral student at the Peking University Center for Life Sciences, is the first author of the paper. Dr. Li Yi from School of Psychological and Cognitive Science is the corresponding author. Dr. Fang Fang and Mr. Sio Pan Hoi from School of Psychological and Cognitive Science, as well as Dr. Yuyin Wang from Sun Yat-sen University and Mr. Cheuk Man Lam from Chinese Academy of Science have made important contributions to this paper. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission.

Wang, Q., Hoi, S. P., Wang, Y., Lam, C. M., Fang, F., & Yi, L. (2020, January 9). Gaze Response to Others’ Gaze Following in Children With and Without Autism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/abn0000498